*Special thank you to SDV Law Clerk Oliver Stallmach for contributing to this article.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, escalating the conflict between the two countries to unprecedented levels. Much of the West quickly responded to Russia’s aggression by levying some of the most severe sanctions in history on Russia’s government, companies, and wealthy citizens, including Vladimir Putin.1 Within a week, reports indicated that these sanctions had already significantly impacted the Russian economy, with the Ruble dropping to historic lows, the Russian Central bank more than doubling interest rates, and S&P Global downgrading Russia to a “junk” rating.2

Of course, given Russia’s reputation at the forefront of the use of antagonistic cyber-attacks through state-sponsored and affiliated means, this has led many to speculate that Russia may institute retaliatory cyber-attacks against the West.3 On February 26, 2022, just days after Russia’s invasion, the Department of Homeland Security released a memo detailing recent examples of destructive malware currently being deployed against organizations in Ukraine that highlights this threat.4

Unfortunately, Russia’s historical use of these channels has been seemingly indiscriminate and has heavily impacted the private sector, domestically and abroad. Fortunately, this historical precedent also provides a window to understand how the cyber insurance market should respond to these potential attacks.

Cyber policies vary dramatically in form, but less so in overall scope. Although they use drastically different language and policy structure to delineate coverage, they tend to insure most of the same general risks, with differences in scope often attributable to nuanced distinctions. Several of these nuances are especially relevant in the current global climate.

Lessons from NotPetya

Russia has already provided a case study for a future attack. Therefore, the insurance industry has already experienced what the risk profile of such an attack might look like. On June 27, 2017, the world witnessed one of the most destructive instances of malware ever deployed, commonly known as “NotPetya.”5 The NotPetya attack is generally understood to have been a state-sponsored cyber-attack by Russia to disrupt foreign investment into Ukraine.6 As the attack infiltrated Ukrainian networks, it also spread across Europe and impacted many companies in the private sector in the process. For example, Merck & Co., Inc. (Pharmaceuticals) suffered losses of $870 million, Mondelez International, Inc. (Snacks) suffered $188 million in losses, and FedEx European subsidiary TNT Express (Shipping and Logistics) suffered $400 million in losses. Because the NotPetya attack was not limited to merely shutting down computer systems, the impacts were far-reaching, even preventing employees from entering their physical offices through some computer-controlled doors.7 NotPetya demonstrates not only the massive losses companies can face when targeted by a cyber-attack, but also the usage for modern cyber-attacks, which can be deployed to disrupt regional trade and, in turn, as a tool to exert political influence. It also illustrates the global economic impact a targeted attack on a single country has.

The possible manifestations of these attacks are diverse and unpredictable. There are far too many specific nuances in the many manuscript coverage forms available in the market to attempt to broadly address all of the coverage concerns that could be implicated by a Russian cyber-attack. However, there are some broad, high-level considerations that can foreclose coverage entirely, even if an insured has purchased coverage under otherwise appropriate insuring agreements.

War, Terrorism, and Cyber Terrorism Provisions

At the forefront of any claim stemming from a possible Russian retaliatory cyber-attack will be the policy’s war and/or terrorism exclusions and how those policy provisions define and account for acts of cyberterrorism. Cyber insurance is still a relatively new market, meaning many aspects of coverage are still continuously evolving.

Early cyber policies often contained war and/or terrorism exclusions reflective of those in many other lines of insurance, sometimes with carve-backs for cyber terrorism and sometimes with no mention of terrorism whatsoever. Many policies exposed the insured to risk for any warlike or hostile action other than a clearly terroristic act conducted by a non-state – and often non-state affiliated – actor. Subject to the language of the particular policy at issue, of course, those policies likely would not have protected an insured facing a Russian retaliatory cyber-attack today. Further still, they may not have protected an insured facing a hostile or warlike action unless there was a clear terroristic purpose behind it, based on the policy’s pertinent definitions.

For example, the formerly common London-based Cyber Suite Insurance Policy form excluded “Acts of Terror,” but carved back coverage for acts of “Cyber Terrorism.” In that form, the definition of “Cyber Terrorism” included acts of individuals or organizations but did not expressly include acts on behalf of a government. While that omission may have created an ambiguity, leaving the insured an opportunity to argue for why a government act should satisfy the definition, it remained unclear and invited dispute.

The cyber insurance market continues to evolve, and this coverage issue has improved for policyholders in the process. Policies – particularly those at the higher end of the market – have begun to offer protection for state-sponsored cyber terrorism, even when a cyber-attack is connected to war. Consider, for example, the Zurich Cyber Insurance Policy (form U-SPR-300-A-CW (09/18)). The Zurich form contains a war exclusion, but then carves back coverage for “Cyberterrorism.” Relevant here, the Zurich form defines “Cyberterrorism” as follows:

[T]he use of information technology to execute attacks or threats ... by any person or group, whether acting alone, or on behalf of, or in connection with, any individual, organization, or government…

This definition expressly extends coverage to cyber-attacks on behalf of a government. Further, the definition goes so far as to clarify that the attack can be “in furtherance of financial, social, ideological, religious, or political objectives.” Under the Zurich policy form, the war and terrorism framework expressly covers the type of potential cyber-attack Russia may launch in retaliation for the economic sanctions imposed by the United States and its allies.

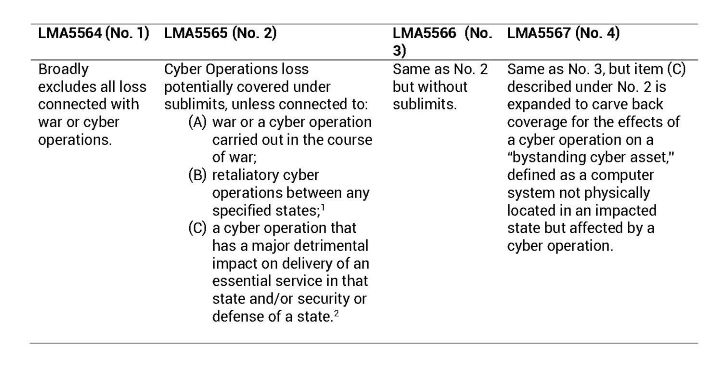

While progress on this issue has generally trended in the policyholder’s favor, some carriers are actively working to claw back some of these coverage gains. This is highlighted by the recent Lloyd’s Market Association’s announcement of plans to release four new standardized model war exclusions for cyber policies.8 The four exclusions range from highly to somewhat restrictive. They are triggered by events of war or “cyber operations,” defined as “the use of a computer system by or behalf of a state to disrupt, deny, degrade, manipulate or destroy information in a computer system of or in another state.” The following table illustrates the exclusions’ applications in the event of cyber loss connected to “war” or “cyber operations”:

Additional attacks similar in nature to NotPetya would not obviously fit within the scope of these Lloyd’s exclusions. However, as a silver lining to policyholders, the Lloyd’s proposal puts the onus of proof on insurers to prove the loss meets the parameters of the exclusion, as the burden of proving application of an exclusion falls on the insurer. This imposes the obligation to show the attribution of the attack to the state on the insurer, which can be a difficult burden to satisfy.

The Critical Importance of Cyber Security for Coverage

Another facet of cyber coverage that has evolved significantly over time is the requirement that the insured maintain certain cyber security protections as a condition of coverage. Early cyber policies often restricted coverage through broad and sometimes vague limitations. For example, an early policy form restricted coverage for any loss arising out of a security flaw in a program that had not previously been proven successful in a live environment for a continuous period of 12 months. These requirements were often non-specific and difficult to ensure compliance, even by an attentive IT team.

As cyber-attacks became increasingly common, cyber insurers became much more knowledgeable about what protections make the most significant difference in avoiding security breaches. For example, any insured who has recently renewed a cyber policy is likely aware of the importance of multi-factor authentication. Instituting these protections is critical, not only for securing coverage in the first place, but also for maintaining it, as such protections are often part of the application process required to place the policy and conditions to an insured’s right to recover under the policy. A failure to maintain and consistently upkeep or troubleshoot a security system that was part of the cyber insurer’s decision-making in placing and pricing the policy can jeopardize coverage if a lapse in that system plays a role in the loss.

The Insured’s Physical Computer System

Part of the reason for such stringent controls is the power of malware to spread rapidly throughout a corporate network from a single computer and impair the insured’s computer systems, both digitally and physically. For example, in Mondelez Int’l, Inc. v. Zurich Am. Ins. Co., NotPetya rapidly spread from just two servers on the insured’s network to 1,700 servers and 24,000 company workstations.11 Although this firm did not handle the Mondelez case, our experience representing policyholders in similar claims, where malware has spread rapidly through a network, has been that the threat of such a rapid spread repeating often requires not only “scrubbing” the network, but also fully replacing the insured’s physical computer systems, because of the threat of reinfection of the entire scrubbed network from reconnecting a single terminal with dormant surviving malware.

This risk to the insured’s physical assets is underappreciated in the cyber insurance market. In some claims, the costs to replace the insured’s physical workstations far outpace the costs incurred for forensics, breach response, and other coverages traditionally contemplated in cyber policies. Accordingly, the policy’s definition of “computer system” (or equivalent term) is critical, as this will likely define the extent of the physical equipment the policy covers. Common discrepancies include failing to properly account for the ownership/lease status of such equipment, identify the operators of such equipment, and address employees’ personal equipment where it is used on behalf of the insured.

One of the challenges in determining whether coverage exists for the physical replacement of the insured’s computers is the lack of consistency in how the coverage exists in cyber policies. One policy may cover the cost as part of the “extra expense” necessary to restore the insured’s business operations to normal capacity, while another might contain a separate insuring agreement just for physical replacement costs. When this risk is covered, it will typically extend to replacing to the same degree that existed prior to the loss, with some possible exceptions where, for example, the insured’s existing system is outdated and cannot be replaced without directly exposing the insured to the same risk that caused the loss.

The Impact of OFAC

The United States Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) has the power to restrict who United States citizens can legally engage in transactions with. Because many cyber-attacks take the form of “ransomware,” in which malware restricts or blocks access to the insured’s computer system or digital assets to extort payment from the insured, OFAC restrictions are a vital consideration for insureds faced with potentially making such demanded payments.12 If the receiving individual or entity is OFAC-sanctioned, the insured can face civil penalties on a strict liability standard (i.e., knowledge of the recipient’s OFAC-sanctioned status is not required) for making the payment.

Numerous Russian entities and individuals have been designated by OFAC as sanctioned actors since before the Ukraine invasion. However, the United States’ recent economic sanctions against Russia included additional prohibitions on transactions between United States citizens and numerous other Russian entities and individuals.13 Accordingly, insureds facing any cyber-attack involving extorted payment to a third party should exercise heightened awareness to ensure they are not subjecting themselves to liability for civil penalties, which cyber policies typically will not cover. The Department of the Treasury’s “Updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments” provides information regarding how to contact appropriate government agencies to confirm a payment will not violate OFAC sanctions.14

Other Lines of “Silent” Cyber Coverage

Although the insurance industry has increasingly shored up its position that coverage for cyber incidents should be limited to cyber policies, exceptions to that general paradigm still slip through the cracks. This phenomenon is generally referred to as “silent” cyber coverage. That is, coverage for cyber risks that satisfy the insuring terms of policies not tailored specifically to covering cyber risks. In many instances, the issues closely parallel the same issues that drive disputes under cyber policies.

In National Ink & Stitch, LLC v. State Auto Property & Casualty Co., an insured found “silent” cyber coverage for physical replacement costs under a property policy. There, the District of Maryland found that the property policy covered damage sustained by a computer system in a ransomware attack.15 The court held that the policyholder’s loss of computer data and software was covered and the loss of functionality of the computer system was covered. The court reasoned that (1) there was physical damage to computer software because the software was rendered unusable by the ransomware attack and (2) “physical damage” was not restricted to the physical destruction or harm of computer circuitry and included loss of access, loss of use, and loss of functionality.

In Merck & Co. Inc. v. Ace American Ins. Co., the policyholder sued its commercial property insurers to recover losses arising out of NotPetya after the insurers denied coverage based on a war exclusion.16 The New Jersey Superior Court ultimately held that the war exclusion was meant to apply to armed conflict and could not be used to deny coverage for the policyholder’s losses. The opinion further reasoned that the insurers would need to clarify the language of their war exclusions to put companies like the insured on notice that cyber-attacks wouldn’t be covered. Similarly, the Mondelez case, venued in Illinois, centers on the application of a war exclusion in a property insurance policy.17

Insureds have also found success targeting commercial crime policies. For example, in Medidata Solutions, Inc. vs. Federal Insurance Company and American Tooling Center, Inc. vs. Travelers Casualty & Surety Co., decided in the Second and Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals, respectively, insureds succeeded in obtaining coverage under commercial crime policies for losses resulting from computer fraud.18 Depending on the language of the war exclusion in the policy at issue, crime coverage could be another resource in a Russian cyber-attack scenario.

Takeaway

Cyber-attacks are inherently unpredictable. As new means of attack become increasingly prevalent, security to address them becomes more robust, leading the means of attack to change and become more sophisticated. This self-perpetuating process makes the cyber market incredibly volatile, as the industry tries to get and keep its arms around a constantly changing set of problems. The added complexity of having a state-sponsored actor perpetrating the attacks only complicates this problem. Given these uncertain times, Western companies should be taking necessary precautions to protect themselves and minimize their exposure in the event they are affected by a Russian retaliatory cyber-attack or any other kind of cyber loss. Insureds should carefully review their cyber programs with their brokers, IT professionals, coverage counsel, and other related consultants to ensure their protection is robust, accounts for these critical issues, and is flexible enough to account for the unpredictable.

For more information contact Will S. Bennett at WBennett@sdvlaw.com or Avery J. Cantor at ACantor@sdvlaw.com.

____________________________________________________________

1Sanctions Swing Toward Putin Himself as Ukraine Anger Grows, Associated Press News (Feb. 26, 2022), https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-vladimir-putin-joe-biden-boris-johnson-business-bfc6f804d960962cdbd0cf9071580a11.

2Natasha Turak, Russia Central Bank more than Doubles Key Interest Rate to 20% to Boost Sinking Ruble, CNBC (Feb. 28, 2022, 7:26 AM EST), https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/28/russia-central-bank-hikes-interest-rates-to-20percent-from-9point5percent-to-bolster-ruble.html; 3Nishara Karuvalli Pathikkal, Taru Jain, Rodrigo Campos, S&P Drags Russia’s Rating Deeper into Junk Territory, Reuters (Mar. 3, 2022, 5:19 PM PST), https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/sp-drags-russias-rating-deeper-into-junk-territory-2022-03-03/.

3Microsoft Digital Defense Report, Microsoft (Oct. 2021), https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/business/microsoft-digital-defense-report.

4U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Sec. Agency, Alert (AA22-057A), Destructive Malware Targeting Organizations in Ukraine (Mar. 1, 2022), https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa22-057a.

5David Bisson, NotPetya: A Timeline of a Ransomware, Tripwire (Jun. 28, 2017), https://www.tripwire.com/state-of-security/security-data-protection/cyber-security/notpetya-timeline-of-a-ransomworm/.

6Zack Whittaker, US Charges Russian Hackers Blamed for Ukraine Power Outages and the NotPetya Ransomware Attack, TechCrunch (Oct. 19 2020, 10:09 AM PDT), https://techcrunch.com/2020/10/19/justice-department-russian-hackers-notpetya-ukraine/.

7Andy Greenberg, The Untold Story of NotPetya, the Most Devastating Cyberattack in History, Wired (Aug. 22, 2018, 5:00 AM), https://www.wired.com/story/notpetya-cyberattack-ukraine-russia-code-crashed-the-world/; Kim S. Nash, Sara Castellanos, Adam Janofsy, One Year After NotPetya Cyberattack, Firms Wrestle with Recovery Costs, The Wall Street Journal (Jun. 27, 2018, 12:03 PM EST), https://www.wsj.com/articles/one-year-after-notpetya-companies-still-wrestle-with-financial-impacts-1530095906.

8Patrick Davison, Cyber War and Cyber Operation Exclusion Clauses, Lloyd’s Market Association (Nov. 25, 2021), https://www.lmalloyds.com/LMA/News/LMA_bulletins/LMA_Bulletins/LMA21-042-PD.aspx.

9“Specified states means China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, UK or USA.”

10Note: “retaliatory” and “major detrimental impact” are undefined.

11Mondelez Int’l, Inc. v. Zurich Am. Ins. Co., No. 2018-L-011008 (Ill. Cir. Ct. Oct. 10, 2018).

12Updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments, U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury (Sep. 21, 2021), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/ofac_ransomware_advisory.pdf.

13Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Treasury Prohibits Transactions with Central Bank of Russia and Imposes Sanctions on Key Sources of Russia’s Wealth (Feb. 28, 2022), https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0612.

14U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments (Sept. 21, 2021), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/ofac_ransomware_advisory.pdf.

15National Ink & Stitch, LLC v. State Auto Prop. and Cas. Ins. Co., 435 F.Supp.3d 679 (D. Md. 2020).

16Merck & Co. Inc. v. Ace Am. Ins. Co. et al, No. L-002682-18 (N.J. Super. Ct. Aug. 2, 2018).

17See FN 11, supra.

18Medidata Solutions Inc. v. Federal Ins. Co., 729 F.App’x 117 (2nd Cir. 2018); Am. Tooling Ctr., Inc. v. Travelers Cas. and Sur. Co. of Am., 895 F.3d 455 (6th Cir. 2018).

Posted on Tuesday, March 15, 2022

Posted on Tuesday, March 15, 2022